The local newspaper reported that the declaration of the First World War caused traders in Poole to close early because people were ordering large quantities of food. A voluntary Food Economy Campaign was introduced at the beginning of the war but the heavy loss of merchant shipping to German U-boats and raiders meant that legislation had to be introduced to cover hoarding, price control and, eventually, rationing. Profiteering was a concern after the war ended. A Culture volunteer on the Poole History Centre First World War project looks at rationing and profiteering during and after the First World War.

The Food Hoarding Order of 1917 made it a criminal offence for a household to have more than 14 days of food that would be needed under normal circumstances. Fines of the order of £200 could be given at a time when the typical wage was £4 to £5 a week. There were no reported instances of hoarding in Poole but the local newspaper did have articles on cases elsewhere in the country. In one remarkable instance, 157 lbs (71kg) of sugar, 110 lbs (49.5kg) of beans, and 60 lbs (27kg) of rice were discovered in a house. What dismayed the inspectors was the waste as much of it had become mouldy and inedible.

One option at a time of uncertainty was to grow your own. Poole was one of the first towns in the country to have war allotments and the War-time Allotments Committee met for the first time during the spring of 1915. Allotments were organised on land lent by the Council at Ladies Walking Field (15 plots), in Longfleet on land lent by Lord Wimborne (30 plots) and on land in Upper Parkstone lent by Mr Colman (16 plots). A registration fee of 1s (5p) was charged but there was no rent.

It was only in 1916 that the Government recognised the value of allotments. The Cultivation of Lands Order was introduced which authorised the Board of Agriculture to take over unused land for food production. Locally, the war-time allotments scheme was a great success and had expanded to around 200 plots by 1916 and only a year later had grown to 1000 plots from Hamworthy to Bourne Valley. The need was highlighted when the local newspaper reported In March 1918 that Dorset had produced 12 000 tons of potatoes, but consumed 20 000 tons, and an appeal was put out for ‘everyone to grow potatoes’ – the end of the war saw 1400 allotments in the Poole area.

The Poole Borough Allotments Association had looked after allotments in the Borough before the war and there was feeling by some that the War-time Committee was ‘antagonistic’ towards them. Land was being freely made available to the Committee and no rent was being charged. It was, however, accepted that the land would probably be returned to its former owners at the end of the war, as happened at Ladies Walking Field. Other sites were taken over for house building but around a 1000 still remained with an uncertain future. It was decided that the Allotments Association would take over those that were to remain as allotments and that an ‘economic’ rent would be charged.

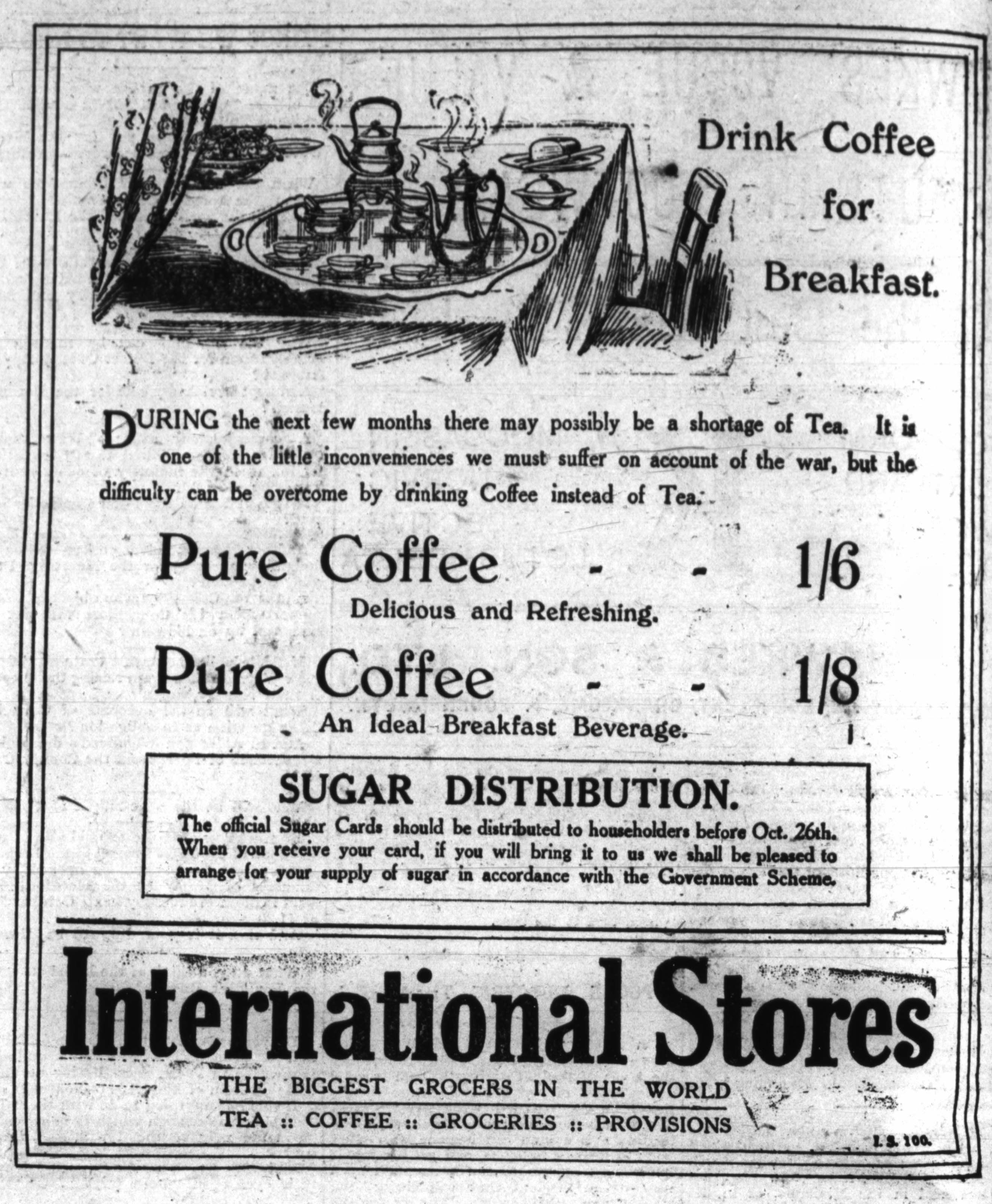

Shortages inspired retailers to advertise alternatives. An advert appeared in October 1917 from one retailer who suggested drinking coffee as an alternative to tea which was in short supply.

Large ports, such as Southampton, were considered vulnerable and Poole was put forward as an emergency port. A cargo service from Channel Islands to Hamworthy started operating from 1915 to import potatoes for distribution throughout the country via the Hamworthy branch railway line. An extra 70 men were hired by the port because of the extra trade. Much of the work was done in poor light because lighting in sensitive coastal areas, such as Poole, was controlled by the Defence of the Realm Act.

An interesting social history aspect to the First World War relates to food at a time when it was suggested a woman could get by on ‘tea and toast’ while a man needed ‘beef and beer’. One advert during the war even promoted the idea that a cup of cocoa could help a working woman by turning a biscuit into a meal. A visit by Poole councillors in September 1916 to the Royal Ordnance Factory at Holton Heath reported that a ‘good lunch’ for 7d (3½ p) was to be had in the canteen. For many women a canteen meal was the first time they had a regular good meal and being in employment meant they also had access to money. School Medical officers in London noted in 1918 that, despite food shortages, the number of children ‘in a poorly nourished condition’ was less than half of those in 1913.

Sugar was rationed in January 1918 but continuing problems over food supply resulted in a much wider rationing scheme. The local newspaper reported that long queues formed outside butchers and grocers as more food was added to the list to be rationed. It was noted that being a regular at a shop was ‘advantageous’. Meanwhile it was claimed that some people were attempting to visit different shops in order to purchase more than was reasonable. There were also reports of milk being diluted with water.

The local newspaper reported in June 1918 that 3000 people were to be employed on the printing and delivery of an estimated 63 million rationing books. The ration book had a white cover for the name of retailer, an orange page for sugar, blue for fats, four red pages for meat and bacon, brown/blue if other foods were to be rationed in the future and a green one for reference. The design was aimed at making forgery ‘a matter of some difficulty’.

Rationing was not without its problems and, in particular, the meat ration was contentious. Those who worked in the heavy industries such as steel, mining and shipbuilding wanted a ration quantity that reflected the arduousness of their work. The debate even extended to whether those in the military who worked in offices should get the same as those in other roles. The workers at one London construction site refused to extend the working day to 7pm unless their meat ration was increased and a similar situation occurred in other places. Concerns over the increasing social unrest resulted in the Cabinet recommending that the Prime Minister meet with newspaper editors to explain the reasons why rationing was needed so as to better inform the general public.

A National Communal Kitchen scheme was set up with the aim of providing food at cost to those who struggled and in January 1918 it was proposed to create two kitchens in Poole. The local project was not successful and there were complaints to the local newspaper over the length of time it was taking to set them up and the scheme was abandoned in April 1918.

Rationing motivated companies to offer alternative products. One retailer suggested spaghetti in tomato sauce with cheese, for which no ration card was needed, as an alternative to meat! Shortages of coal inspired one manufacturer to offer a product for cleaning clothes that avoided the need to heat up water.

Legislation was put in place to control food prices. In April 1917, a local market gardener was charged with selling potatoes at a higher price than regulated. A consumer wanted to buy 2 lbs (900g) of potatoes at Poole Market and was offered 1 lb. When she got home she found the bag contained 3 potatoes and the rest were turnips. The defendant argued that children had knocked over a table and the potatoes and turnips had got muddled up. The Poole Police Court was unimpressed and fined the defendant £2.

In February 1918, a consumer claimed that the ½ lb (225g) of China tea he had bought for 2s (10p) from a Poole High Street shop was of poor quality and claimed analysis had shown it to be 20% used tea and 2% something other than tea. The case went to court but was dismissed as another analyst could not repeat the result.

In 1919, and with the war over, the Government responded to public pressure to relax controls but had to re-introduce them because prices started going up and poor quality food was being found on sale. The Food Hoarding Order also still applied.

Shortages after the war led to the Profiteering Act of 1919 and the Poole Council set up a Committee in November 1919. Someone convicted of an offence under the Act could be fined up to £50 or be sent to prison for up to one month. Anybody who wanted to complain about profiteering in the Poole Borough had to write to W.G. Granger, Clerk of the Committee at 217 High Street within 4 days of the purchase.

One case in early December 1919 involved a local hotel which charged 2s (10p) for two teacups of milk which was considered excessive and the proprietors were ordered by the Profiteering Committee to refund 1s (5p). In September 1920, a complaint was made against a fruiterer by a Lower Parkstone resident who claimed they were overcharged for half a pound of apples. The case was dismissed.

1920 was dominated by world food shortages caused by a combination of the war and the 1918 flu pandemic which had a catastrophic effect on production and transport. Butter, wheat, tea and sugar were in short supply and the ration for sugar in Britain was reduced from 8oz (225g) per person per week to 6oz. Prior to the war, Britain consumed around 1.8 million tons of refined sugar of which only half was supplied by British sugar refiners. The rest came from the Continent. Alternative supplies were sought from Cuba and Java during the war but these were dependent on the merchant ships getting through. Peace may have broken out in November 1918 but sugar from the Continent was planted in May and harvested in October – which meant there was a world shortage of sugar. In contrast, there was a glut of meat in Britain from Australia and New Zealand but the country did not have sufficient cold storage and prices had to be reduced so that it did not go to waste.

The Poole Food Control Committee had its last meeting in June 1920.150 breaches of regulations had been reported to the committee with 97 convictions resulting in fines totalling £109 6s 6d. In April 1918, 38,066 ration cards had been issued and 42,791 were in circulation when the committee closed down. As an indication of the level of trade in the Poole area, 185 tea dealers, 130 sugar retailers, 132 butter retailers, 142 margarine retailers and 35 butchers had been ‘controlled’ by the Committee by the end of 1917.

Examples of breaches of food controls included a High Street retailer who was fined 5s (25p) for selling ¼ lb of toffee for 9d when it should have been 8d. He said he was unaware that the price of sweets was controlled. A High Street butcher was fined £5 for selling a rabbit for 2s (10p) when it should have 1s 9d (8½p). Another trader was fined 5s (25p) for not displaying a price list.

The continuing concerns over profiteering led to the Profiteering (Amendment) Act 1920 which widened the scope of the earlier Act to include items on hire or hire purchase as well as nearly thirty items such as milk, flour, meat, coal, bread, fish, poultry, bacon and marmalade. While the aim of the Amendment was to control the cost of living, it was also believed that legislation was needed because the ‘psychological aspect of [profiteering was of] very considerable importance’. The Profiteering (Amendments) Act ended on 19 May 1921 and Poole Council announced, as did other councils, the disbanding of the Profiteering Committee.